The Therapeutic Use of Precious and Semi-Precious Stones

We found this information and practice of crushing precious stones for medical purposes quite fascinating, and while we do not recommend you begin crashing up and eating your gemstones for medicinal purposes, perhaps you might be inspired to study a little deeper into the benefits of such a practice.

We also hope to inspire a nonbeliever in the properties of minerals, to take a second look. There is a long history of using stones not just as jewelry, but for other beneficial purposes. We will explore the history of this practice.

THE medicinal use of precious stones may be traced back to very ancient times. It has been conjectured that their employment for such purposes was introduced to Europe from India, whence many of the stones were derived. Nevertheless, the earliest evidence we have rather points to Egypt as the source, and, indeed, it appears that in early Egyptian times the chemical constituents of the stones were much more rationally considered than at a later period in Europe.

The Ebers Papyrus, for instance, recommends the use of certain astringent substances, such as lapis-lazuli, as ingredients of eye-salves, and hematite, an iron oxide, was used for checking hemorrhages and for reducing inflammations. Little by little, however, superstition associated certain special virtues with the color and quality of precious stones, and their virtues were thought to be greatly enhanced by engraving on them the image of some god, or of some object symbolizing certain of the activities of nature. Later still, the science of astrology, most highly developed in Assyria and Babylonia, was brought into combination with the various superstitions above indicated, so that the image was believed to have much greater efficacy if the engraving were executed when the sun was in a certain constellation or when the moon or some one of the planets was in the ascendant at the time.

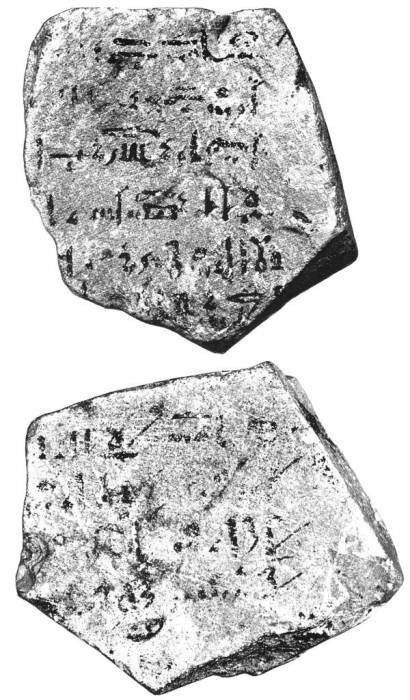

The image, dates from about 1600 b.c., the period of the Ebers Papyrus, and gives directions for preparing certain remedies from precious stones. While the interpretation of this text offers considerable difficulty, one version finds in it the statement that lapis-lazuli—the “sapphire” of the ancients—was used for the wealthy, and malachite for those of limited means.

A distinction is often made between the talismanic qualities of precious stones for the cure or prevention of disease and the properly medicinal use of them as mineral substances.

In the former case the effect was attained by merely wearing them on the person, while in the latter case they were reduced to a powder, which was dissolved as far as possible in water or some other liquid and then taken internally.

As, however, the end to be attained is the same whether the stone be worn or taken internally as a powder or liquid, it seems more logical to treat of both these methods of therapeutic use together.

The belief in the curative properties of precious stones was at one time universal among all those to whom gems were known. When we read to-day of the various ills that were supposed to be cured by the use of these gems, we find it difficult to understand what process of thought could have suggested the idea of employing such ineffectual remedies. It is true that the constituents of certain stones can be absorbed by the human body and have a definite effect upon it, but the greater part of the elements are so combined that they cannot be assimilated, and they pass through the system without producing any apparent effect.

In ancient and medieval times, however, other than chemical agencies were supposed to be efficient in the cure of diseases, and the primitive animistic conception of the cause of illness, and hence of the therapeutics of disease, long held sway among those who practised the medical art.

Remedies were prized because of their rarity, and also because it was believed that certain spiritual or planetary influences had aided in their production and were latent in them.

Besides this, the symbolism of color played a very important part in recommending the use of particular stones for special diseases.

Red

This may be noted in the case of the red or reddish stones, such as the ruby, spinel, garnet, carnelian, bloodstone, etc. These were thought to be sovereign remedies for hemorrhages of all kinds, as well as for all inflammatory diseases; they were also believed to exercise a calming influence and to remove anger and discord. The red hue of these stones was supposed to indicate their fitness for such use, upon the principle similia similibus curantur.

Yellow

In the same way yellow stones were prescribed for the cure of bilious disorders, for jaundice in all its forms and for other diseases of the liver.

Green

The use of green stones to relieve diseases of the eye was evidently suggested by the beneficial influence exerted by this color upon the sight. The verdant emerald represented the beautiful green fields, upon which the tired eye rests so willingly, and which exert such a soothing influence upon the sight when it has been unduly strained or fatigued. One of the earliest, probably the very earliest reference in Greek writings to the therapeutic value of gems, appears in the works of Theophrastus, who wrote in the third century before Christ. Here we are told of the beneficial effect exercised by the emerald upon the eyes.

Blue

The sapphire, the lapis-lazuli, and other blue stones, with a hue resembling the blue of the heavens, were believed to exert a tonic influence, and were supposed to counteract the wiles of the spirits of darkness and procure the aid and favor of the spirits of light and wisdom. These gems were usually looked upon as emblems of chastity, and for this reason the sapphire came to be regarded as especially appropriate for use in ecclesiastical rings.

Purple

Among purple stones, the amethyst is particularly noteworthy. The well-known belief that this gem counteracted the effects of undue indulgence in intoxicating beverages is indicated by its name, derived from μεθύω—“to be intoxicated,” and the privative α, the name thus signifying the “sobering” gem. It is not unlikely that a fancied resemblance between the prevailing hue of these stones and that of certain kinds of wine first gave rise to the name and to the idea of the peculiar virtues of the amethyst.

Ancient use of powdered crystals and stones in medicines

When precious stones are to be used in medicine, they must be pulverized until they are reduced to a powder so fine that it will not grate under the teeth.

A teacher of this art noticed of his student…..

“…. I begged a medical student, who was lodging with me, to pass an entire month in grinding some of these stones. I gave him emeralds, jacinths, sapphires, rubies, and pearls, an ounce of each kind. As these stones were rough and whole, he first crushed them a little in a well-polished iron mortar, using a pestle of the same metal; afterward he employed a pestle and mortar of glass, devoting several hours each day to this work. At the end of about three weeks, his room, which was rather large, became redolent with a perfume, agreeable both from its variety and sweetness. This odor, which much resembled that of March violets, lingered in the room for more than three days. There was nothing in the room to produce it, so that it certainly proceeded from the powder of precious stones.”

Examples of some stones used for medicinal purposes:

Emeralds

- The emerald was employed as an antidote for poisons and for poisoned wounds, as well as against demoniacal possession.

- If worn on the neck it was said to cure the “semitertian” fever and epilepsy.

- By the Hindu physicians of the thirteenth century the emerald was considered to be a good laxative. It cured dysentery, diminished the secretion of bile, and stimulated the appetite. In short, it promoted bodily health and destroyed demoniacal influences. In the curious phrase of the school the emerald was “cold and sweet.”

- Furthermore, the wearer was protected from the attacks of venomous creatures, and evil spirits were driven from the place where emeralds were kept.

Topaz

The use of a topaz to cure dimness of vision is strongly recommended by St. Hildegard. To attain the desired end the stone was to be placed in wine and left there for three days and three nights. When retiring to sleep, the patient should rub his eyes with the moistened topaz, so that this moisture lightly touched the eyeball. After the stone had been removed, the wine could be used for five days

A Roman physician of the fifteenth century was reputed to have wrought many wonderful cures of those stricken by the plague, through touching the plague sores with a topaz which had belonged to two popes, Clement VI and Gregory II. The fact that this particular topaz had been in the hands of two supreme pontiffs must have added much to the faith reposed in the curative powers390 of the stone by those upon whom it was used, and this faith may really have helped to hasten their recovery

The sapphire

- should have been regarded as especially valuable for the cure of eye diseases serves to illustrate the wide-reaching and persistent influence of Egyptian thought, and the curious transformations through which an originally reasonable idea may pass in the course of time. We have already noted that the sapphire of the ancients was our lapis-lazuli, and in the Ebers Papyrus lapis-lazuli is given as one of the ingredients of an eye-wash. This ingredient is believed to have originally been the oxide of copper sometimes called lapis Armenus, a material possessing marked astringent properties, and which might be used to advantage in certain morbid conditions of the eye. Lapis-lazuli, another blue stone, was later substituted because of its greater intrinsic value, its similarity of color rendering it equally efficacious according to primitive ideas on this subject. When, however, in medieval times, the name sapphire came to signify the blue corundum gem known to us by this designation, the special curative virtues of the lapis-lazuli were transferred to this still more valuable stone

The diamond

- The diamond was believed to afford protection from plague or pestilence, and a proof of its powers in this direction was found in the fact that the plague first attacked the poorer classes, sparing the rich, who could afford to adorn themselves with diamonds. Naturally, in common with other precious stones, this brilliant gem was supposed to cure many diseases.

- An Austrian nobleman, who for a long time had not been able to sleep without having terrible dreams, was immediately cured by wearing a small diamond set in gold on his arm, so that the stone came in contact with his skin

- The fact that in this case, as in many others, the stone was required to touch the skin, proves that the effect supposed to be produced was not altogether magical, but in the nature of a physical emanation from the stone to the body of the wearer.

Source:

“The Folk-Lore of Precious Stones,” Chicago, 1894

Middleton, “Engraved Gems of Ancient Times,” Cambridge, 1891, p. 151.

Zelia Nuttall, “The Fundamental Principles of Old and New World Civilization,” Cambridge, Mass., 1901, p. 195. Archæological and Ethnographical Papers of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University, vol. ii.